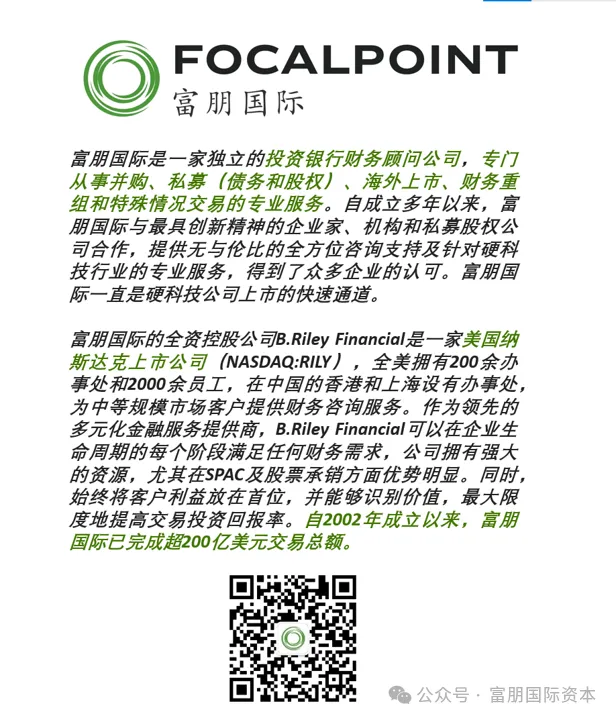

When reviewing SPAC data from recent years, one curve always stands out. In July 2020, Bill Ackman launched his SPAC — Pershing Square Tontine Holdings (PSTH) — and, with a US$4 billion raise, pulled the entire SPAC market’s average IPO size up to its peak.

Picture: SPAC listings and average offering size, July 2020–2025; Bill Ackman’s US$4 billion SPAC pushed the average IPO size to a five-year high in July 2020 (red box). Source: FocalPoint

This transaction became almost a mirror of an era — at the very height of the SPAC frenzy, a Wall Street titan stepped in personally and created the largest SPAC in history. Years later, as the tide receded and SPACs normalized, the summit Ackman raised still sits at the top of the curve like a permanent marker.

Behind that peak lies a story of ambition, innovation, gamesmanship — and regret.

01 Bill Ackman — Hedge-Fund Titan and Billionaire

Bill Ackman (full name William Albert Ackman), born in 1966 into an affluent Jewish family in New York, is a renowned U.S. hedge-fund manager and the Founder & CEO of Pershing Square Capital Management, L.P.

Picture:Bill Ackman. Source: The Economist.

In 1992, at the age of 30, Ackman founded his first hedge fund, Gotham Partners, and rose to prominence through activist investing. In 2004, he set out again, founding Pershing Square Capital Management, known for “concentrated positions + deep research + active ownership.” He not only invests in companies’ shares but often enters boards, challenges management teams, and even pushes for strategic or structural change.

Ackman’s investing career has seen dramatic ups and downs. He suffered heavy losses shorting Herbalife, and once had short-term paper losses exceeding US$400 million on Netflix; yet he also generated substantial long-term returns by taking large positions in high-quality names such as Hilton, Restaurant Brands International, and Chipotle. His style can be summarized in two words: bold and focused. Once he bets, he concentrates — his top ten holdings have long accounted for 90%+ of fund assets — and in Q2 2025 that figure reached 99.32%, putting almost all the eggs in just a few baskets.

In 2020, as sponsor, he launched the SPAC Pershing Square Tontine Holdings (PSTH), raising US$4 billion — still a landmark case in the SPAC market.

02 A US$4 Billion SPAC: The Backdrop

Compared with today’s more common US$200 million SPAC sizes, a US$4 billion SPAC is colossal.

1) Macro environment: post-pandemic liquidity + SPAC boom

Rates at historic lows. In March 2020, the Federal Reserve made two emergency rate cuts in two weeks, taking the federal funds target range from 1.50%–1.75% down to 0%–0.25% — effectively bringing the risk-free rate to near zero.

Flood of liquidity. Beyond cutting rates, the Fed launched unlimited QE (buying Treasuries and MBS in the hundreds of billions per month), expanding its balance sheet from US$4.1 trillion to US$8.9 trillion by 2021. The consensus on Wall Street: too much money, too few opportunities.

Investor psychology. Against this backdrop of ultralow rates and excess liquidity, SPACs became a “high value-for-money tool” in investors’ eyes: funds go into trust first, with the chance to ride a sponsor’s M&A arbitrage later. For a star sponsor like Bill Ackman, the market chased hard — almost a “buy with your eyes closed.”

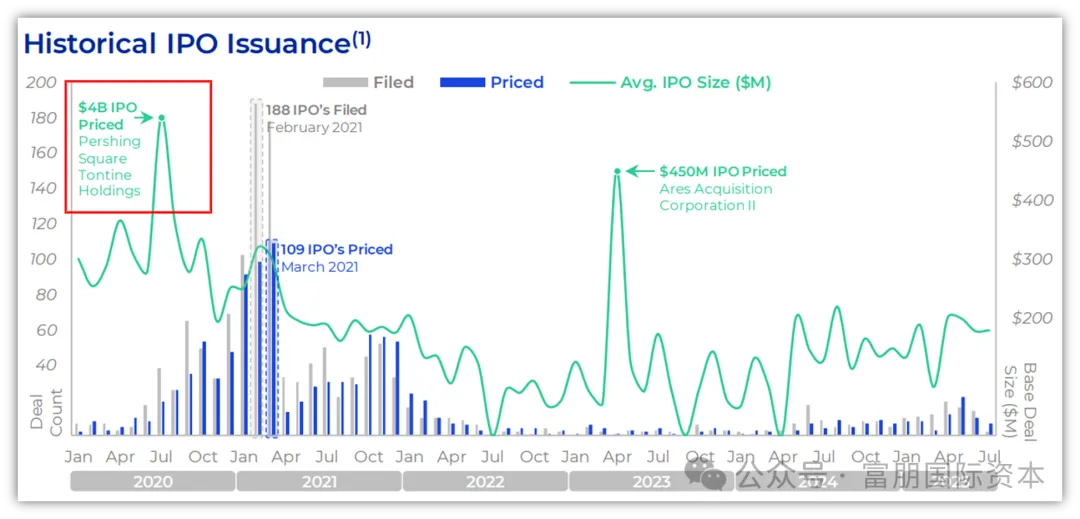

2) PSTH basics: the largest ever, with a higher price point

Listing timing and size. On July 22, 2020, Pershing Square Tontine Holdings (PSTH) IPO’d on the NYSE: 200,000,000 units × US$20 = US$4.0B, setting a then-record for SPACs. Notably, while SPACs typically price at US$10 per unit, Ackman wanted PSTH to attract more long-term institutional investors (e.g., pensions, sovereign wealth funds) rather than short-term arbitrage retail, so he set a US$20 threshold to raise the screen for participation.

Underwriters: Citigroup; Jefferies; UBS Investment Bank

Underwriters’ counsel: Ropes & Gray LLP

U.S. counsel: Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft LLP

Auditor: Marcum LLP

Picture:Pershing Square Tontine Holdings (PSTH) “Use of Proceeds.” Source: SEC.

3) “Investor-friendly” design (different from a typical SPAC)

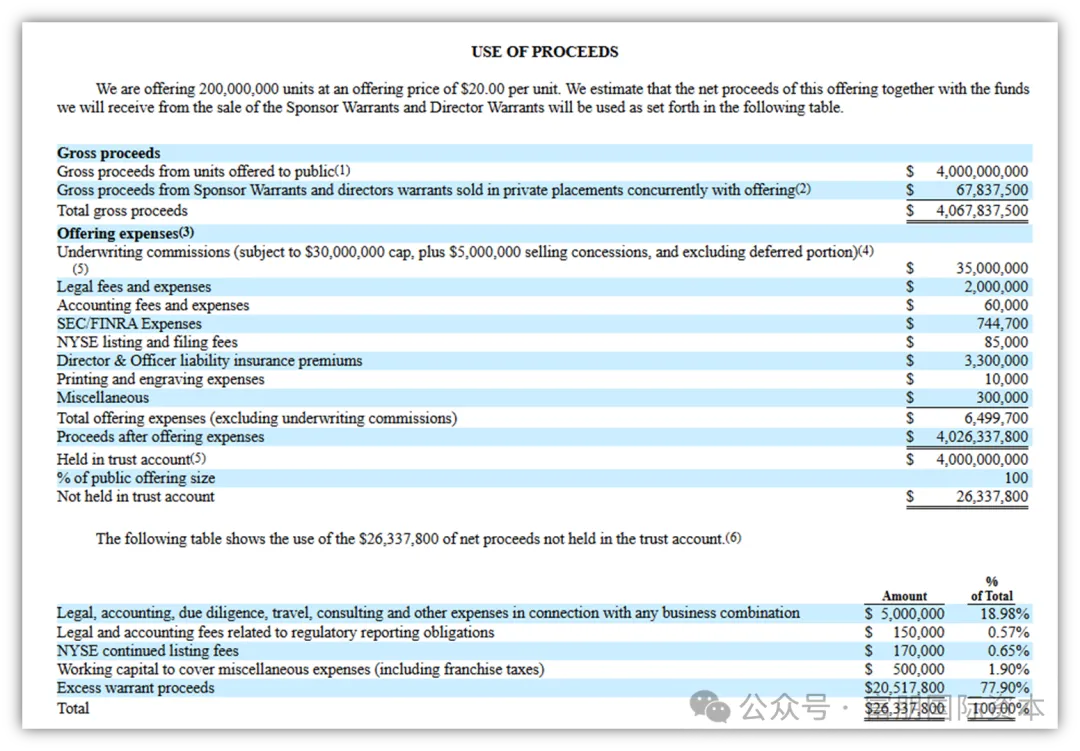

No traditional founder promote. The sponsor did not take the standard 20% founder shares; instead, the sponsor purchased sponsor warrants at fair value and committed additional real capital via a Forward Purchase Agreement (FPA).

Forward Purchase Agreement. Pershing Square committed US$1–3 billion to be invested at US$20 per unit at closing of the business combination (each unit: 1 share + 1/3 warrant), giving PSTH total “firepower” of US$5–7 billion (US$4B IPO + US$1–3B FPA).

PSTH mechanisms (reducing redemptions, rewarding long-term holders). Each IPO unit = 1 share + 1/9 Distributable Redeemable Warrant. There were also “2/9 tontine” distributable warrants (total 44,444,444), to be allocated pro rata to holders of record after a deal announcement and across redemption/exchange arrangements, with only non-redeemers/continuing holders ultimately entitled — designed to lower redemption rates and stabilize the capital structure.

Sponsor/Director warrant constraints. Sponsor-purchased warrants could not be transferred/exercised until three years after the initial business combination, further aligning incentives with long-term performance.

Image: Schematic of an FPA’s basic flow. Note: figure is illustrative; specific terms are transaction-dependent. Source: FocalPoint.

4) Why were expectations for PSTH so high?

Scale + firepower. A US$4B trust plus US$1–3B FPA was effectively aimed only at mega-cap, high-quality targets.

Investor-tilted terms. No promote, warrants delayed, anti-redemption mechanics — Ackman described this as an “investor- and M&A-friendly” SPAC.

Celebrity effect. Markets had near-blind faith in Ackman’s ability to find a large, premium target. PSTH was hailed at birth as a template for “SPAC 2.0.”

03 The Attempted Combination with Universal Music Group (UMG)

If PSTH’s US$4 billion was a mega-bet, then the ideal counterpart Ackman identified was surely Universal Music Group (UMG).

🎵 The world’s largest music empire

UMG is one of the global “Big Three” labels, home to storied imprints such as Interscope, Island, Capitol, Def Jam, and Motown, and to star artists including Taylor Swift, Drake, and Ariana Grande. In the music industry, UMG alone carries half the weight.

Picture: mage: UMG promotional poster featuring Taylor Swift, Drake, Ariana Grande, among others. Source: UMG.

At the time, Vivendi, UMG’s controlling shareholder, planned to spin UMG out for a separate listing on the Euronext Amsterdam, with an estimated valuation around US$35 billion — a dream opportunity for any investment firm.

🤝 PSTH’s plan

Ackman hoped to have PSTH acquire 10% of UMG. In other words, PSTH investors would not receive shares in a newly listed U.S. company in the traditional SPAC sense; rather, through PSTH they would indirectly hold shares of a music empire listed in Europe.

In Ackman’s vision, this was a groundbreaking “SPAC 2.0”:

-

Investor funds remained safe (the trust mechanism still applied);

-

Target asset quality was exceptionally high (the world’s No. 1 music company);

-

There was no need to fear valuation bubbles or fraud risks.

It looked like a win-win.

⚖ A sharp turn

However, the problem was that the “innovation” went too far.

Regulatory concerns. The SEC and NYSE believed the deal did not align with a SPAC’s intent. A SPAC’s mission is to take an unlisted company public via a merger, whereas PSTH would only buy a minority stake and the target would separately IPO in Europe. Investors who bought PSTH would end up indirectly owning a small portion of another company, which regulators viewed as misaligned with the SPAC framework.

Investor expectation gap. Investors expected a controlling combination + U.S. listing, but got minority equity + European listing — a huge mismatch. PSTH’s share price fell sharply on the news.

Structural complexity. Ackman later admitted the overall structure was too complex for the market to accept.

Picture: Bill Ackman. In July 2022, at the end of PSTH’s 24-month life, Ackman announced the liquidation of the US$4 billion SPAC. Source: CNBC.

❌ The outcome

In 2021, UMG proceeded with Vivendi’s plan and listed in Amsterdam.

PSTH’s SPAC-merger plan collapsed.

For PSTH, missing UMG effectively meant losing the only project capable of supporting a US$4 billion vehicle. It never found a suitable alternative and ultimately liquidated in 2022, returning funds to investors.

04 Takeaways: SPAC Size Selection Matters

We analyze pros and cons of SPAC size from both the sponsor and target perspectives.

1) Sponsor perspective

Launching a large SPAC (US$150 million+)

Advantages:

-

Deeper capital pool: Can cover profitable mid-cap or growth companies with some international footprint, and provide stronger cash at closing.

-

Greater investor comfort: A larger trust helps ensure the post-combination market cap is not too small, supporting liquidity and research coverage.

Disadvantages: -

Narrower target set: A US$150–200 million SPAC often implies an EV target range of US$0.5–1.0 billion — not too large (or funds won’t suffice), not too small (or mismatch).

-

Capital pressure: Higher risk capital outlay by sponsors, taking on more risk.

Launching a smaller SPAC (US$50–150 million)

Advantages:

-

Higher flexibility: Broader target universe, especially growth-stage SaaS, hard tech, health-care services.

-

Narrative upside: Smaller market cap can allow the target to drive share-price elasticity through growth milestones.

Disadvantages: -

Refinancing pressure: Limited trust is more sensitive to redemptions, requiring PIPE or forward purchase arrangements in advance.

-

Weaker secondary liquidity: Free float may be insufficient post-listing, leading to volatility.

-

Limited brand backing: Smaller capital pool may be less attractive to mid- to large-cap targets.

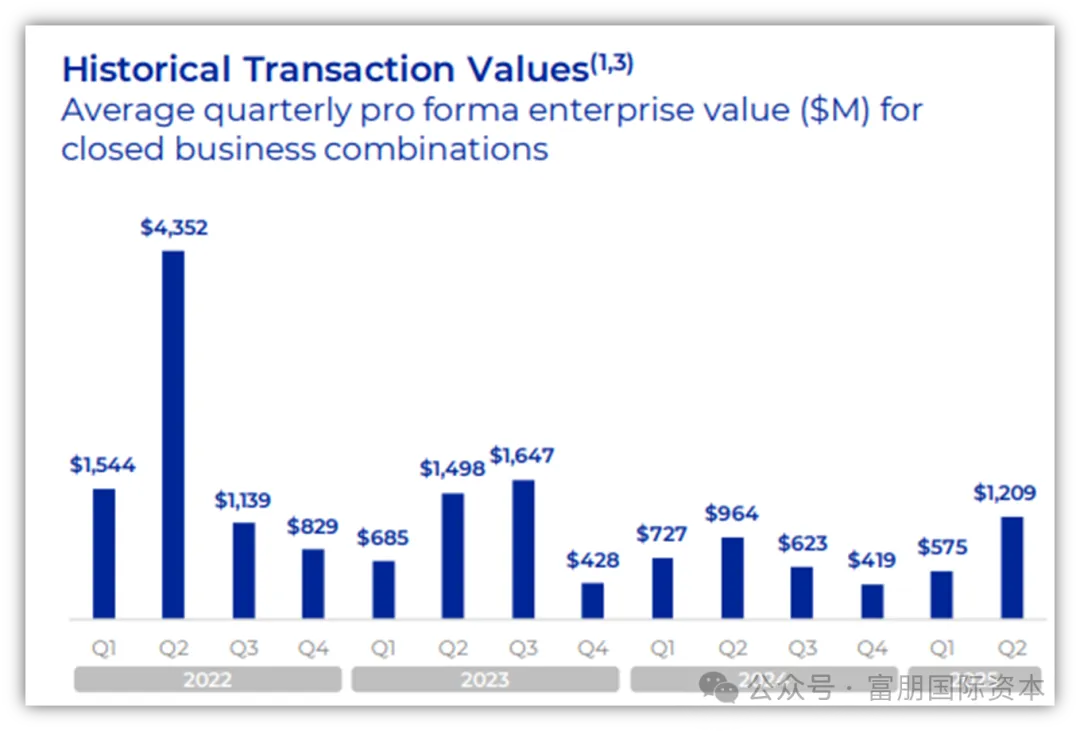

Picture: Average de-SPAC deal size by quarter over the past three years; size has risen for two consecutive quarters, prompting sponsors to launch larger SPACs. Source: FocalPoint.

2) Target perspective

Merging with a large SPAC (US$150M+)

Advantages: Strong one-off financing capacity, higher institutional recognition, and easier follow-on fundraising.

Disadvantages: Greater valuation pressure and higher equity dilution for the combined company.

Merging with a small SPAC (US$50–150M)

Advantages: Flexible and fast, with efficient negotiation and execution; suitable for companies that need a listing but do not require a large one-time raise.

Disadvantages: May still require PIPE or secondary financing post-listing depending on development needs, creating longer-term capital pressure.

03 Why Companies Should Plan Ahead

As the SPAC market warms, more capital and professional institutions are entering the field. For companies with overseas financing and listing plans, early preparation is critical:

-

Window advantage: When sentiment turns, early movers are more likely to attract investor attention and secure better valuations.

-

Policy and regulatory readiness: While new rules raise the bar, they also increase transparency. Early planning enables smoother handling of audit, compliance, and disclosure.

-

Capital-structure optimization: With liquidity improving, SPACs — and the de-SPAC process — can offer flexible financing that supports long-term growth.

In this context, waiting until the market is “fully hot” may mean facing stiffer competition and higher costs. Entering early and planning proactively are key to securing the initiative in the next SPAC wave.

In 2024, Fupeng International has successfully completed five SPAC listings, setting an annual record for a single institution in the industry.

Enterprises with clear listing plans can contact Fupeng International for negotiation. With our cutting-edge capital structure design capabilities, we help innovative enterprises seize the historic opportunities in the SPAC 2.0 era.